Poetry and the Creative Mind

One of the best ways to get the creative juices flowing is to take a break from trying to get the creative juices flowing. By stepping away from a task, you prevent your mind from fixating on a single idea or solution, becoming more receptive to fresh thoughts in the process. Researchers call this incubation, but in everyday terms it's more like forgetting the stuff that doesn't work in the hopes of accessing something that does.

New research suggests that this process of creative forgetting doesn't require a long incubation period, but can occur more or less in real-time. Call it micro-incubation; or, more formally, inhibition. In a series of experiments, psychologists Benjamin Storm and Trisha Patel of UC-Santa Cruz demonstrate that the very act of brainstorming new ideas can inhibit the recovery of old ones, and that as this instant forgetfulness increases, so too does a person's creativity.

"The results of the present research suggest that thinking and forgetting are intrinsically connected—that to think of new ideas can cause the forgetting of old ideas, and that such forgetting may play an essential role in promoting the ability to think creatively," Storm and Patel conclude in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition.

To test creative forgetfulness, the researchers first simulated creative fixation. They did this by showing test participants eight everyday objects (such as a newspaper) and listing some baseline typical uses for each object (such as gift-wrapping). For half the objects, they also asked the test participants to generate as many alternative uses for it as possible in 1 minute—a standard test of creativity known as the "alternative uses task."

Using newspaper as an example, the idea behind this experiment was that coming up with an alternative use like kitty litter required test participants to overcome a potential mental block in gift-wrapping. What the researchers wanted to find out was whether a creative mind conquers that fixation by inhibiting it so much that it's forgotten. So at the end of the entire experiment, the researchers asked participants to recall as many of the baseline typical uses (e.g. gift-wrapping) for each object as they could.

The results offered a glimpse of incubation in motion. Participants recalled fewer baseline typical uses for an object when they had to come up with new alternative uses, compared to when they merely read the list of typical uses and didn't perform the "alternative uses task." In other words, something about coming up with kitty litter led the mind to discard gift-wrapping so completely that it couldn't be recalled. Storm and Patel took the findings as a sign of "thinking-induced forgetting."

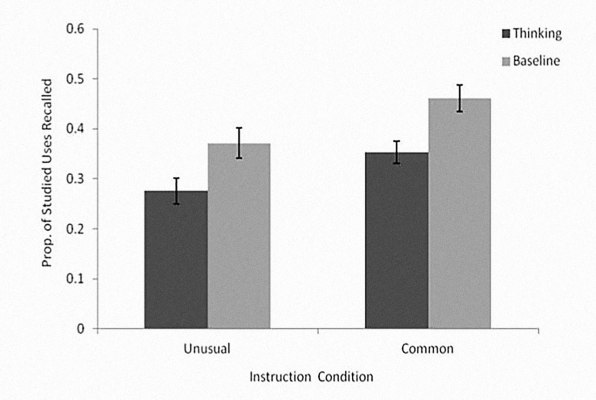

The inhibition effect occurred no matter how creative the participants were trying to be. Thinking-induced forgetting held true for participants who were instructed to generate common alternative uses, such as kitty litter, or highly unusual ones, such a paper toga. Notably, though, recall was worse for those who tried to be highly unusual with their alternatives, as if the extra mental energy needed for extreme originality heightened inhibition.

In subsequent experiments, the researchers built on these initial results. One test showed that creative forgetting was so strong that it occurred even when participants received partial cues during the recall test; for example, seeing g____-w____ wasn't enough to remember gift-wrapping. Another test found no signs of creative forgetting when participants expanded on, rather than blocked out, baseline typical uses (below)—a result that suggests inhibition can distinguish between fixation and inspiration.

"If existing ideas are helpful in facilitating the thinking of new ideas, then those ideas do not appear to be susceptible to thinking-induced forgetting," the researchers report.

As a capper, Storm and Patel lumped all the experimental results together for a combined analysis. They found that participants who showed greater levels of forgetting generated alternative uses rated as significantly more creative than their less-forgetful peers. By inhibiting potential fixations, they conclude, "participants were able to explore a more diverse and original search space, leading them to generate more creative uses."

Now for some qualifications. From a scientific perspective, the research isn't perfect: the experiments have pretty small sample sizes, and the "alternative uses task" has been criticized as a poor proxy for creativity (is using newspaper as a toga original, or just silly?). It's also far from certain that the results truly represented inhibition; maybe the participants did block out old ideas to consider new ones, or maybe the process of considering new ones interfered with old memory.

From a general perspective, it's hard to know how to apply the findings. Anyone can take a break when they hit a mental block, but how exactly would someone develop the ability to inhibit fixations on the fly? In that sense, the research serves much more as a theoretical explanation of creativity than as a practical guide to nurturing it.

Those caveats aside, the research remains intriguing as another step toward better understanding the creative process. It also provides some solace to creative types who've had the unfortunate experience of losing a great idea because they didn't write it down. There may, in fact, be something worse than forgetting a great idea: not being able to forget that bad ones blocking it.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3039090/how-a-forgetful-mind-can-be-a-more-creative-mind